Script

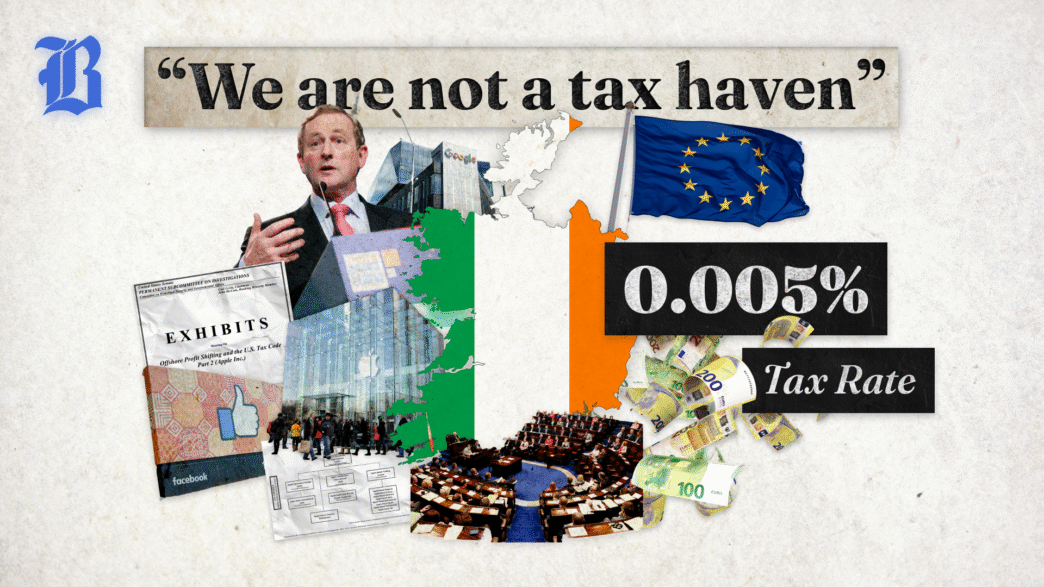

In 2016 the EU ordered Apple to pay €13 billion to Ireland, accusing the tech giant of illegally evading tax. Apple quickly appealed the decision, claiming it had not broken the law, despite having been paying an effective tax rate of just 0.005%. Surprisingly, the Irish government also took Apple’s side, claiming that Apple had done nothing wrong. But the ruling was finalised in 2024, forcing Ireland to receive the billions of euros it had fought so hard against receiving. But why had Ireland decided to take Apple’s side, and how had the tech giant managed to pay almost zero corporation tax for over a decade?

The answer to both questions is the same: Ireland is a tax haven. Which is a commonly known fact, yet Ireland continuously claims not to be one. To understand why, first we need to discuss what tax havens are, and how they work.

A tax haven is a country or state that allows companies or individuals to pay little or no tax. Apple’s minute effective tax rate over 10 years demonstrates this, and is far from Ireland’s 12.5% corporation tax rate at the time. Apple, along with many other large US multinationals, managed to pay such low tax rates through a loophole known as the Double Irish.

By shifting intellectual property rights to an Irish subsidiary that was registered for tax in Bermuda, companies benefited from Irish tax treaties with the US and the 0% Bermuda tax rate simultaneously. This subsidiary would then lease intellectual property rights to a second Irish subsidiary, which collected revenue from customers outside the US. This operating company funnelled most of the taxable profits to the Bermuda-resident subsidiary using royalty fees.

But to avoid Irish withholding tax on these payments, the money was first routed through a Dutch subsidiary, before it landed in Bermuda where it conveniently paid no tax. This loophole was particularly effective for digital and knowledge-based firms, as their main assets were intellectual property which could be shifted across borders far more easily than physical capital. In 2011, Google Ireland Ltd. accounted for 92% of all sales outside of the US. This meant US multinationals like Apple and Google paid very low effective tax rates on their foreign profits, which they could then repatriate tax-free to their parent company through further loopholes.

The opportunity to boost post-tax profits meant many US multinationals set up headquarters in Dublin, Ireland’s capital. As a result, Ireland benefited from the investment and employment that these headquarters brought. Also, while effective tax rates could be low, when taken from a base of worldwide shifted profits, these could still be beneficial for the Irish government. But the EU’s case against Apple served as a threat to the many other corporations based in Dublin that were carrying out similar practices. The Irish State’s decision to side with Apple can be seen as reassurance for other US corporations, trying to stop them from leaving Dublin when facing the EU’s regulatory tightness.

Publicly, the Irish State’s argument for contesting the EU’s ruling was that Apple had not actually broken any laws, or received any preferential treatment. The case was a closely contested one, with the decision being overruled by the European General Court in 2020, then reinstated again finally by the higher European Court of Justice in 2024.

This is because tax planning – the act of managing finances to reduce tax exposure – often blurs the line between tax evasion and tax avoidance. Tax avoidance is legally reducing taxes, while tax evasion is illegally not paying taxes that they are obligated to. Apple’s case was at least tax avoidance, as demonstrated by the extremely low effective tax rate. But the EU’s case rested on whether this was just achieved through avoidance, or crossed the line to evasion.

Apple had used an adapted version of the Double Irish, using separate branches inside a single company. The approval of this tax setup was ruled as an illegal agreement between Ireland and Apple, that gave it a competitive advantage over other companies. So after the final ruling, Apple was ordered to pay back the €13 billion in illegal tax benefits it obtained from the setup.

This was seen as a huge victory, because corporate tax evasion through tax havens is rarely successfully prosecuted, but causes huge damage. This is because the key component of multinational tax planning is profit shifting. Multinationals are charged corporation tax on the profits that they make. But if a subsidiary makes no profit or a loss, it does not pay corporation tax to the government of the country it operates in. It will still have to pay other taxes, but if a firm can reduce its corporation tax burden, its post-tax profits can become much higher.

So, multinationals shift profits from countries with high corporation tax to low tax havens by using loopholes like the double Irish. The double Irish was an intellectual property profit shifting strategy, while other methods using debt and transfer pricing exist too. These profit shifting strategies result in subsidiaries in countries with high corporation tax artificially reporting little to no profitability, and therefore paying little to no corporation tax. Meanwhile the tax haven subsidiaries report making all the profit, but also pay little to no corporation tax because of the haven’s low or zero tax rate. The multinational firm gains, but the high tax countries lose out on tax revenue. As multinational corporations often hold huge market shares of industries, this means the tax loss from tax haven profit shifting can be huge.

In the US, tax loss from corporate profit shifting has been estimated to be around $80bn a year. Governments that lose out on tax revenue due to tax havens have two options: borrow more or cut spending. Government debt due to constant budget deficits has been rising consistently over recent years. This, paired with interest rates rising from their historically low levels has meant the cost of servicing debt interest has become much more prominent as a proportion of government spending, creating a need for further borrowing or spending cuts.

Rising national debt levels are not primarily caused by losses due to tax havens, crises like the global financial crisis and covid, as well as a general appetite for budget deficits have caused more damage, but tax havens worsen the already growing issue. So there have been calls for cuts in government spending, which often is used for progressive policies like education, transportation and social welfare. So tax havens can have an effect of increasing inequality in this way.

Tax havens can also help facilitate crime. Pure tax havens often have secretive laws that hide information about business conducted in there, hiding the laundering of criminal profits and corruption bribes, and helping the evasion of sanctions. The most prominent scandal in relation to this is the Panama Papers investigation. The report exposed how rich and powerful people across the world, from national leaders to investment fund CEOs, used Panama’s secretive business environment to evade tax and channel illegal funds.

By increasing asset holder returns at the expense of government budgets, increasing inequality, facilitating crime and allowing sanction evasion, most governments see tax havens as a threat that needs to be dealt with. Sometimes this involves changing laws to limit profit shifting, or it can come in the form of retaliation against tax havens to get them to change their laws themselves.

And this is why Ireland doesn’t want to be seen as a tax haven. If it strays too far, the country risks being labelled as an economically rouge state. Being placed on a tax haven blacklist can result in sanctions that force companies to leave the country, which is a large threat when the Irish economy depends so heavily on multinational investment. So the Irish state has to balance its tax policy, keeping haven like characteristics to attract investment, but avoiding becoming a pure tax haven, so it can somewhat deny being one and avoid economic retaliation.

But like the line between tax evasion and avoidance, the line between being a tax haven and not is blurred. The OECD definition has 4 key identifying factors: No or only nominal taxes, lack of effective exchange of information, lack of transparency and no substantial activities.

At first glance, Ireland doesn’t seem to meet these factors. Its 12.5% corporation tax rates is low, but far from nominal. As a member of the EU and OECD, Ireland exchanges information and is relatively transparent. Multinational’s headquarters in Dublin also carry out substantial management of EU operations, with Google employing over 5,000 staff in Dublin.

But looking deeper, the distortions of the double Irish begin to show a different story. Apple and other MNEs actually paid only nominal effective tax rates. And while Dublin was a significant HQ, Google Ireland Ltd. accounting for 92% of Google’s sales outside the US is out of proportion to the actual economic activity taking place in Ireland.

A more accurate explanation is that Ireland was not a pure tax haven, but contained some tax haven characteristics, like relatively light regulation and Tax legislation that was responsive to MNEs’ needs. And most importantly, Ireland facilitated the use of the pure tax haven Bermuda though the double Irish. Because Ireland itself was not a pure haven it could pretend not to be one, avoiding retaliation from other countries. But it benefited from the investment the loophole brought, and was an accomplice in the damage it caused.

As a result, the EU forced Ireland to close the double Irish loophole in 2014, with incumbent firms given until 2020 when the changes applied. However the end of the double Irish wasn’t the end of Ireland’s tax haven era, but the start of a new one. Multinationals began shifting Intellectual Property onshore to Ireland, to take advantage of the Capital Allowances for Intangible Assets and other schemes to continue paying low tax rates.

This caused a huge artificial annual increase in Ireland’s GDP of around 30%. It also increased Ireland’s tax revenue, which paired with Apple’s fine, has created a large surplus in the government’s budget. But the country is still facing struggles with a housing crisis and high cost of living. And with the economy operating at near full capacity, even though the Irish government has the money, increasing its spending may simply cause further inflation.

New international tax regimes, like the OECD minimum tax, have threatened Ireland’s position to continue attracting tax related investment. But President Trump has fought hard against international taxation of US corporations, meaning Ireland will likely continue business as usual for US firms.

And the Irish state’s message will stay the same, claiming they are not a tax haven. And yes, maybe Ireland doesn’t meet all of the criteria, and many other western states carry out similar tax related practices. But for a country that’s in the top 10 of a global tax haven ranking, pretending not to be one is not fooling anybody.

References

BBC (2016a). Apple fights back with appeal against EU Irish tax ruling. BBC News. [online] 19 Dec. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-38362434.

BBC (2016b). Apple tax: Irish cabinet to appeal against EU ruling. BBC News. [online] 2 Sep. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-37251084.

Campbell, J. (2016). Apple tax ruling ‘a serious blow’ to Irish investment. BBC News. [online] 30 Aug. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-northern-ireland-37219372.

Cioffi, C. (2024). Big Business Ponders Global Tax Strategy as 2025 Cliff Nears. [online] Bloomberg Tax. Available at: https://news.bloombergtax.com/daily-tax-report/big-business-ponders-global-tax-strategy-as-2025-cliff-nears.

Dharmapala, D. (2014). What Do We Know about Base Erosion and Profit Shifting? A Review of the Empirical Literature. Fiscal Studies, 35(4), pp.421–448. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5890.2014.12037.x.

Economist (2023). What’s Weird about Ireland’s GDP? [online] The Economist. Available at: https://www.economist.com/the-economist-explains/2023/10/31/whats-weird-about-irelands-gdp.

Espinoza, J., Webber, J. and Agyemang, E. (2018). Financial Times. [online] @FinancialTimes. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/d6b7d0fd-a41b-45a9-a830-9cacb10c5151.

European Central Bank (2024). Key ECB interest rates | ECB Data Portal. [online] data.ecb.europa.eu. Available at: https://data.ecb.europa.eu/main-figures/ecb-interest-rates-and-exchange-rates/key-ecb-interest-rates.

European commission (2016). State aid: Ireland gave illegal tax benefits to Apple worth up to €13 billion. [online] European Commission. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_16_2923.

Fletcher, O. (2024). Ireland Budget: Government Delivers Bonanza on Corporation Tax Boon. [online] Bloomberg.com. Available at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-10-01/ireland-delivers-giveaway-budget-on-corporation-tax-boon.

Foxe, K. (2017). Department of Finance anger over ‘wholly inaccurate’ Oxfam report painting Ireland as a tax haven – Ken Foxe. [online] Kenfoxe.com. Available at: https://www.kenfoxe.com/2017/04/department-of-finance-anger-over-wholly-inaccurate-oxfam-report-painting-ireland-as-a-tax-haven/ [Accessed 15 Jul. 2025].

FRED (2025). Effective Federal Funds Rate. [online] Stlouisfed.org. Available at: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/FEDFUNDS.

FT Editorial Board (2025). Trump’s assault on the global corporate tax regime. [online] Financial Times. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/9a7c3f74-cb95-491a-9ec0-a10987b21634.

Gravelle, J.G. (2022). Tax Havens: International Tax Avoidance and Evasion. [online] Congressional Research Service. Available at: https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R40623.

Harding, L. (2016). What are the Panama Papers? A guide to history’s biggest data leak. [online] The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/news/2016/apr/03/what-you-need-to-know-about-the-panama-papers.

Honohan, P. (2021). Is Ireland really the most prosperous country in Europe? Central Bank of Ireland, [online] 2021(1). Available at: https://www.centralbank.ie/docs/default-source/publications/economic-letters/vol-2021-no-1-is-ireland-really-the-most-prosperous-country-in-europe.pdf.

Kelly, L. (2016). Ireland – an Attractive Location in a Post BEPS-World. International Tax Review, 27(1), pp.60–63.

Leahy, P., Horgan-Jones, J. and Bray, J. (2024). Budget 2025: ‘Bonanza’ budget that pumps billions into economy repeats Ireland’s past mistakes, State watchdog warns. [online] The Irish Times. Available at: https://www.irishtimes.com/your-money/2024/10/01/budget-2025-bonanza-budget-that-pumps-billions-into-economy-repeats-irelands-past-mistakes-states-watchdog-warns/.

Levin, C. and Mccain, J. (2013). PERMANENT SUBCOMMITTEE ON INVESTIGATIONS Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs E X H I B I T S Hearing On Offshore Profit Shifting and the U.S. Tax Code Part 2 (Apple Inc.). [online] Available at: https://www.hsgac.senate.gov/wp-content/uploads/imo/media/doc/EXHIBITS%201-19%20(May%2021%202013)3.pdf.

Loomis, S. (2012). The Double Irish Sandwich: Reforming Overseas Tax Havens. St. Mary’s Law Journal, 43(4), pp.825–854.

McCarthy, J. (2016). Named and shamed — but still in denial that Ireland is a tax haven. [online] Thetimes.com. Available at: https://www.thetimes.com/world/ireland-world/article/named-and-shamed-but-still-in-denial-that-ireland-is-a-tax-haven-plzb0c5sm [Accessed 15 Jul. 2025].

OECD (2025). OECD Data Explorer. [online] Oecd.org. Available at: https://data-explorer.oecd.org/.

Smyth, J. (2018). Ireland boosted by foreign investment. [online] @FinancialTimes. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/85d9d6d2-37af-11e1-897b-00144feabdc0 [Accessed 23 Jul. 2025].

Somerville, J. (2015). Double Irish Finished: How about a KDB? International Tax Journal, 41(1), pp.5–8.

Stewart, J. (2013). Is Ireland a Tax Haven ? [online] Available at: https://www.tcd.ie/triss/assets/PDFs/iiis/iiisdp430.pdf.

Tamma, P. and Agyemang, E. (2024). Trump win puts global corporate tax deal ‘in peril’. [online] Financial Times. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/75cd612d-55e3-41a9-9dee-9602e56137e3.

The Economist (2024). Ireland’s government has an unusual problem: too much money. [online] The Economist. Available at: https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2024/10/31/irelands-government-has-an-unusual-problem-too-much-money.

Tobin, G. and Walsh, K. (2013). What Makes a Country a Tax Haven? An Assessment of International Standards Shows Why Ireland Is Not a Tax Haven. The Economic and Social Review, 44(3), pp.401–424.

USA Spending (2024). USAspending.gov. [online] USAspending.gov. Available at: https://www.usaspending.gov/explorer/budget_function.

Walsh, J. and Bray, J. (2018). We’re not a tax haven, Donohoe tells Davos. [online] Thetimes.com. Available at: https://www.thetimes.com/world/ireland-world/article/were-not-a-tax-haven-donohoe-tells-davos-x7bvfwlpq.

Walsh, K. (2010). The Economic and Fiscal Contribution of US Investment in Ireland. SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1806696.

Waters, R. (2020). Google to end use of ‘double Irish’ as tax loophole set to close. [online] Financial Times. Available at: https://www.ft.com/content/991f11ae-2c51-11ea-bc77-65e4aa615551.

White, A. and Hancock, E. (2024). €13B legal win over Apple made me cry, says shocked EU competition chief. [online] POLITICO. Available at: https://www.politico.eu/article/vestager-legal-win-over-apple-made-me-cry/.

Media References

Creative Commons Photos

“Enda Kenny” by European People’s Party is licensed under CC BY 2.0 https://www.flickr.com/photos/45198836@N04/13537429673

“Election of An Taoiseach, Enda Kenny TD” by Houses of the Oireachtas is licensed under CC BY 2.0 https://www.flickr.com/photos/oireachtas/27042706341/in/photostream/

“Outside the European Court of Justice” by Katarina Dzurekova is licensed under CC BY 2.0 https://flickr.com/photos/128884785@N06/16216011058/in/photostream/

“Apple Store – Fifth Avenue” by Jorge Láscar is licensed under CC BY 2.0 https://www.flickr.com/photos/8721758@N06/7181848534

“Hearings of Margrethe Vestager” by European Parliament is licensed under CC BY 2.0 https://www.flickr.com/photos/european_parliament/48865071413

“Ryosei Akazawa, Scott Bessent, Howard Lutnick and Jamieson Greer” by 内閣府 is licensed under CC BY 4.0 https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ryosei_Akazawa,_Scott_Bessent,_Howard_Lutnick_and_Jamieson_Greer_20250416.jpg

Other Photos

https://unsplash.com/photos/gray-and-white-concrete-building-Un-vHvg5ezU

https://www.pexels.com/photo/buildings-with-waterfront-view-1650882

https://www.pexels.com/photo/buildings-near-open-field-2881393

https://www.pexels.com/photo/european-commission-flags-on-poles-13153479

https://www.pexels.com/photo/white-concrete-bridge-3566191

https://www.pexels.com/photo/european-parliament-in-strasbourg-france-11682403

Newspaper

https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/viewer/bl/0002324/19980201/327/0030